- Global landscape of critical mineral

The global energy transition demands a rapid rollout of renewable technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, electric batteries, and electric vehicles, alongside major upgrades to existing power grids. At the same time, the digital transformation is reshaping economies through the expansion of consumer electronics, the digitalization of everyday life, and the adoption of Industry 4.0 production methods, including industrial robotics and additive manufacturing. These shifts are supported by large-scale growth in data storage and connectivity. Together, they are driving a surge in demand for the minerals and metals that underpin these technologies, requiring an unprecedented increase in the extraction, processing, and recycling of so-called “critical minerals” – the metals essential for green, digital, and advanced manufacturing, even though the term itself is not yet universally defined or adopted.

To date, there is no universally accepted definition or global list of critical minerals. What counts as “critical” differs across countries and regions and depends, among other factors, on their specific position in global supply chains at a given point in time. In practice, minerals and metals are typically classified as critical or strategic based on two main considerations.

First, minerals and metals are often deemed critical when they are significant direct inputs into key current or planned industrial activities but are not available, or are only minimally available, from domestic sources (IGF, 2023). In such cases, countries face high import dependence, particularly when they do not produce the mineral or metal at all. A central element of this definition is supply-chain vulnerability, including exposure to geopolitical, commercial, or logistical risks that could disrupt access. This approach is widely adopted by the European Union, the United States, Japan, and other advanced economies, where the primary policy focus is on securing supply and mitigating disruption risks.

Second, minerals and metals may be considered critical when they are domestically abundant and a country has a strategic interest in leveraging its dominant resource position to gain competitive advantage or to foster domestic industrial development and move up global value chains. In this context, producer countries frequently use terms such as “strategic minerals” or “strategic assets” to emphasize their role as key suppliers in global supply chains. Here, the central policy objective is not just security of supply, but value capture, i.e., maximizing economic returns and industrial upgrading from their resource endowments (IGF, 2023). A growing number of economies including the United States, the European Union, Japan, Australia and Canada have adopted dedicated critical minerals strategies that combine clear lists of strategic materials, substantial public financing, and explicit targets for domestic mining, processing and recycling. While import-dependent economies such as the US, EU and Japan prioritise security of supply and stockpiling, resource-rich countries like Australia and Canada focus on capturing more value through processing, refining and downstream manufacturing. Table 1 illustrates the comparison of policy approaches by resource-rich and import-dependent economies.

Table 1 Country’s strategy for critical mineral supply chain

| Country | Position in supply chain | Primary objectives | Key tools & approaches |

| United States | Import-dependent major power | Secure critical minerals for energy transition, defence and high-tech industries; reduce reliance on China; build resilient, friendshoring supply chains (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2025) | DOE Critical Materials Assessment and list; USGS 50-mineral critical list; large federal funding (loans, grants, tax credits) for domestic mining, processing and recycling; strategic stockpiles; partnerships with allies (U.S. Department of Energy, 2023) |

| European Union | Import-dependent integrated market | Cut strategic dependence on a few suppliers (esp. China); ensure secure, sustainable supply for green and digital transitions | Critical Raw Materials Act with 2030 benchmarks (≥10% extraction, 40% processing, 25% recycling in EU; max 65% from one third country); strategic projects, simplified permitting, diversification toward “trusted partners” (European Commission, 2023). |

| Japan | Import-dependent manufacturing hub | Stabilise supplies of rare metals for autos, electronics and advanced manufacturing, hedge against external shocks. | Long-standing JOGMEC stockpiling system for rare metals; state-backed overseas resource investments; new economic security laws treating critical minerals as strategic materials (Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security, 2023). |

| Australia | Resource-rich, high-governance supplier | Become a leading global producer and processor; capture more value domestically; support allied energy transition. | Critical Minerals Strategy 2023–2030; Critical Minerals Production Tax Incentive (10% of processing/refining costs for 31 minerals); large public finance for processing; strong ESG and permitting frameworks (Australian Department of Industry, Science and Resources, 2023). |

| Canada | Resource-rich, ESG-intensive supplier | Position Canada as a “global supplier of choice” for sustainable critical minerals across the full value chain. | C$3.8 billion Critical Minerals Strategy (2022); support for exploration, mining, processing, recycling and manufacturing; strong emphasis on Indigenous participation and environmental protection (Government of Canada, 2022). |

| Indonesia | Resource-rich, assertive value-adder | Leverage dominant nickel resources to force local processing, attract EV and stainless-steel industries, and increase value added. | Progressive bans on unprocessed nickel ore exports; requirements for domestic processing; priority concessions for companies investing in smelters; revised mining law to reinforce domestic value addition (Phoumin, 2025). |

Source: Author’s elaboration.

- Vietnam and ASEAN in global critical mineral mapping

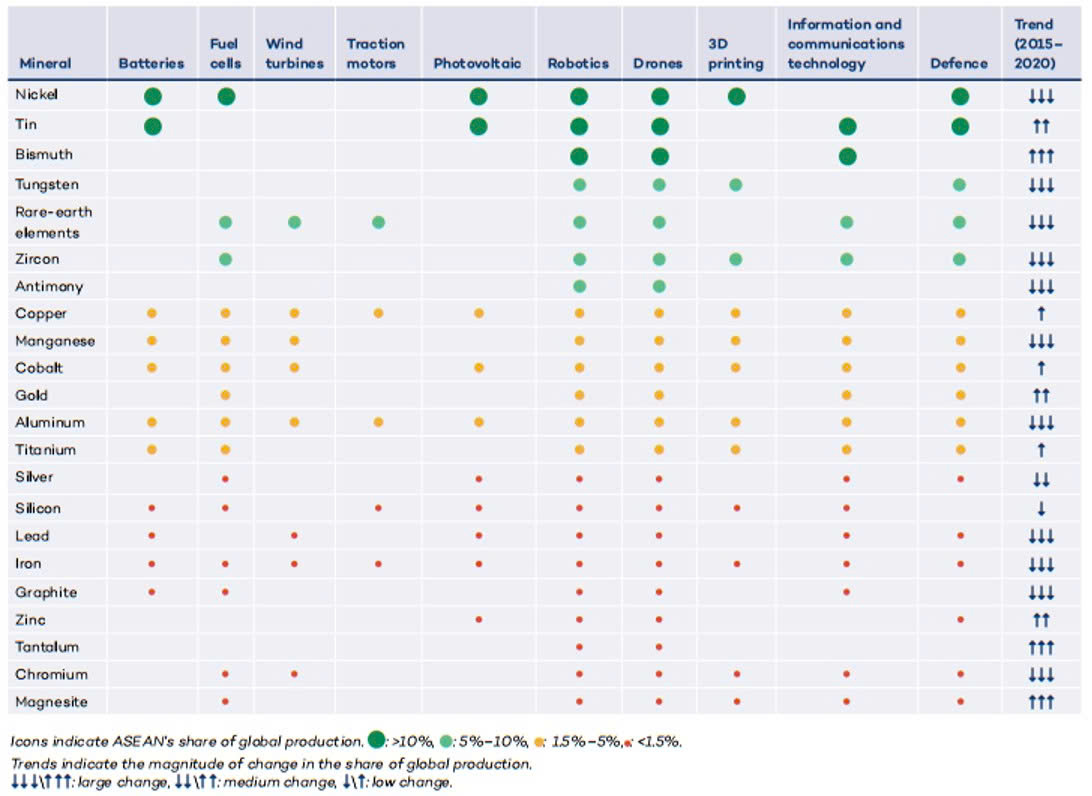

As ASEAN moves toward a much higher deployment of green energy technologies, critical minerals will inevitably become a cornerstone of this transition. Globally, the energy transition is projected to require around 6.5 billion tonnes of end-use materials between 2022 and 2050, with about 95% of this made up of steel, copper, and aluminium (International Energy Agency, 2025). In ASEAN, demand for critical minerals is expected to rise in parallel with this shift: the 7th Edition of the ASEAN Energy Outlook (AEO7) projects renewable energy capacity to reach about 41.5% of total power capacity, and the electric vehicle (EV) fleet to grow to roughly 2.5% by 2025. ASEAN countries have increasingly secured the most key minerals and metals needed for digital and energy transition in the future (Figure 1).

Figure 1. ASEAN’s production of key minerals and their use in energy, digital and defence technologies

Source: Reichl and Schatz, 2022; Bobba et al., 2023

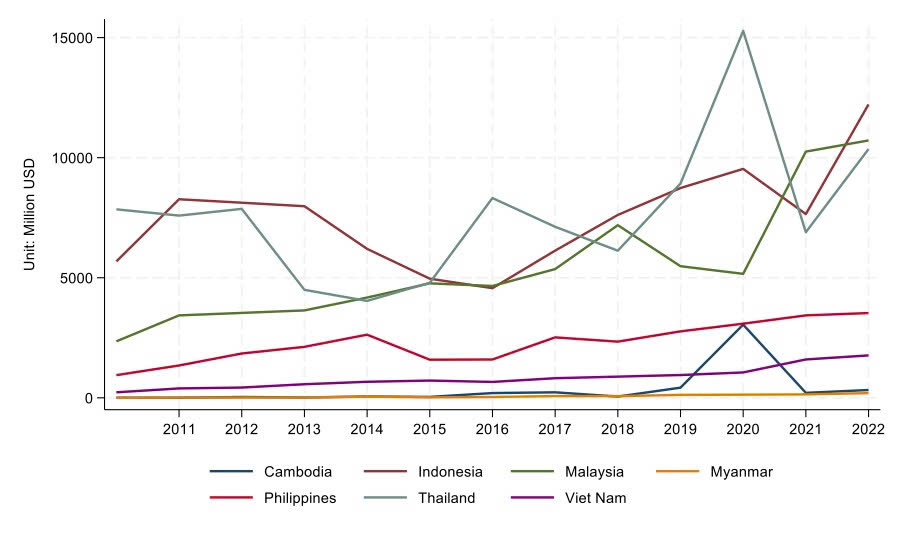

Figure 3 Export of critical minerals of Vietnam and other ASEAN partners

Source: Authors calculation using ADB Trade in Critical Mineral 2023

From 2011–2022, ASEAN trade in critical minerals is clearly dominated by Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, which form the top tier of exporters with flows often above USD 5–10 billion and sharp spikes in several years (notably Thailand in 2016 and 2020, and Malaysia after 2020). The Philippines and Viet Nam sit in a second tier: both start from a much lower base but show a steady upward trend, with Viet Nam’s exports rising from only a few hundred million USD in the early 2010s to around the low billions by 2022.

For Viet Nam specifically, the graph suggests a gradual but persistent expansion rather than boom-and-bust cycles. Unlike Thailand and Indonesia, which experience large year-to-year swings, Viet Nam’s line is smoother, indicating more incremental integration into critical mineral value chains. At the same time, Viet Nam still lags far behind the regional leaders in scale, and only recently begins to close part of the gap with the Philippines. Overall, Viet Nam appears as a mid-sized but rapidly emerging exporter—no longer marginal like Cambodia or Myanmar, yet not yet a core hub comparable to Indonesia, Malaysia or Thailand.

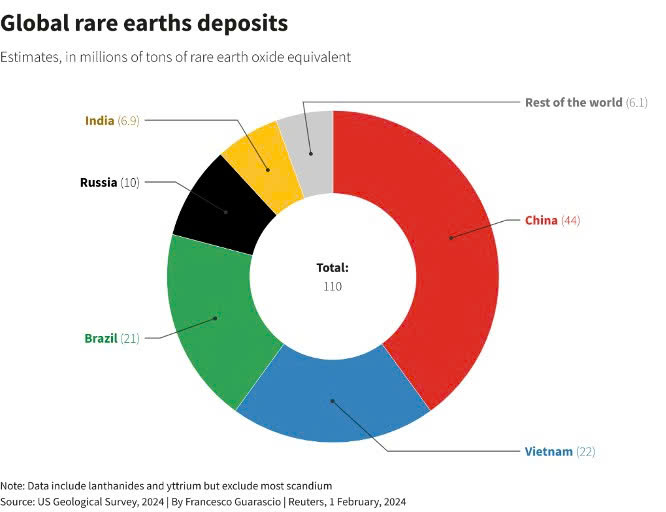

Figure 2 Vietnam rare-earth metal reserves

Vietnam has long been viewed as a “sleeping giant” in rare earth minerals: it holds the world’s second-largest rare earth reserves, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, and already produces several minerals that other countries and regional groupings classify as critical. Yet these resources remain largely underdeveloped, as investment has been constrained by low global prices effectively set by China’s near-monopoly over production and processing, which have made large-scale projects in Vietnam commercially unattractive until recently. In 2022, Vietnam top exports of critical mineral includes Nickel, Fluorspar, Molybdenum, Zinc, Aluminium, unveiling untapped potential of rare-earth metals.

In recent years, growing concerns over supply security have prompted countries such as South Korea, Australia, and Canada to turn to Viet Nam in search of new sources of critical minerals. The United States and Viet Nam have also signed an agreement that includes a technical cooperation plan to better quantify Viet Nam’s reserves of key minerals, particularly rare earths, laying the groundwork for future investment and partnership in this sector. In fact, although Viet Nam has substantial supply potential, its processing and enrichment capacity remains limited, constraining the ability to deliver export-grade raw inputs. Strategic partnerships with high-demand importing countries are therefore essential to upgrade processing technology, improve product quality, and strengthen Viet Nam’s position in critical mineral supply chains.

Viet Nam’s Mineral Resources Strategy to 2020, with a Vision toward 2030, highlights both the sector’s potential and the importance of increasing domestic value addition. However, any definition of “critical” minerals must also reflect the country’s rapid economic growth and the rising material needs of its expanding manufacturing base. This requires systematic assessments of current and projected domestic industrial consumption, to ensure that supplies are secured not only for minerals produced within Viet Nam and ASEAN, but also for metals and minerals sourced from outside the region.

Vietnam has recently overhauled its mining framework through the 2024 Law on Geology and Minerals, which replaces the 2010 Minerals Law and takes effect from 1 July 2025 (VietnamNet, 2025). The new law integrates geology and mining under a single framework, introduces a four-tier classification of mineral resources that explicitly includes rare earth elements in the top (Group I) strategic category, and strengthens planning, licensing, and environmental safeguards to steer the sector toward more sustainable, efficient use of resources. Building on this, draft amendments under discussion go further for critical minerals: they propose to classify rare earths as a “special strategic resource”, centralise authority for exploration, mining and processing at the central government level, and ban the export of unprocessed rare earth ore. The amendments also envisage a dedicated National Strategy on Rare Earths, state-funded geological surveys, and stricter rules on reserves and deposit protection, signalling Hanoi’s intention to tighten control over critical minerals while promoting deeper processing and higher value capture at home.

3. Policy implications

In fact, although Viet Nam has substantial supply potential, its processing and enrichment capacity remains limited, constraining the ability to deliver export-grade raw inputs. Strategic partnerships with high demand importing countries are therefore essential to upgrade processing technology, improve product quality, and strengthen Viet Nam’s position in critical mineral supply chains. There are several implications for Viet Nam’s next steps in enhancing participation in critical mineral value chains:

Prioritise processing and enrichment over raw ore exports

- Link exploration and mining licences to minimum domestic beneficiation and processing benchmarks (e.g. concentrate, oxides, or intermediate materials rather than unprocessed ore).

- Provide targeted fiscal incentives (tax holidays, accelerated depreciation, lower royalties) specifically for investments in processing plants, not just extraction.

- Pilot at least one or two “flagship” processing hubs for rare earths and other critical minerals, with shared infrastructure (power, water, logistics, testing labs) to reduce entry costs.

Leverage strategic partnerships to move up the value chain

- Use Viet Nam’s resource base to negotiate long-term offtake agreements with major importers (US, EU, Japan, Korea), conditioned on onshore processing, technology transfer, and local supplier development.

- Embed knowledge transfer clauses (training, joint R&D, internships) into investment contracts to build a domestic cadre of geologists, process engineers and materials scientists.

Link critical minerals to domestic industrial upgrading

- Integrate critical minerals into a broader industrial strategy for green and digital manufacturing (e.g. EV components, magnets, electronics, grid equipment), rather than treating mining as an isolated sector.

- Use public procurement (for renewables, grid equipment, defence, ICT) to create predictable domestic demand for intermediate products based on Vietnamese-processed minerals.

- Support SMEs and local suppliers in mining regions to participate in supply chains (maintenance services, logistics, engineering), increasing the domestic value captured per tonne of ore.

Improve data, planning, and institutional coordination

- Invest in geological surveys and resource mapping to improve reserve estimates, reduce information asymmetry with foreign investors, and support more strategic decision-making.

- Establish a high-level inter-ministerial taskforce on critical minerals (industry, trade, environment, finance, foreign affairs) to coordinate policies and avoid fragmented decision-making.

- Regularly update Viet Nam’s critical minerals list and strategy to reflect changing global technologies and domestic industrial needs, ensuring that “criticality” is tied to both export potential and domestic consumption.

Reference

Australian Department of Industry, Science and Resources (2023) Critical Minerals Strategy 2023–2030 | Department of Industry Science and Resources. Available at: https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/critical-minerals-strategy-2023-2030 (Accessed: November 8, 2025).

Bobba, S. et al. (2023) Critical raw materials for strategic technologies and sectors in the EU: a foresight study. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2873/58081.

European Commission (2023) European Critical Raw Materials Act. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/green-deal-industrial-plan/european-critical-raw-materials-act_en (Accessed: November 8, 2025).

Government of Canada (2022) Minister Wilkinson Releases Canada’s $3.8-billion Critical Minerals Strategy to Seize Generational Opportunity for Clean, Inclusive Growth – Canada.ca. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/natural-resources-canada/news/2022/12/minister-wilkinson-releases-canadas-38-billion-critical-minerals-strategy-to-seize-generational-opportunity-for-clean-inclusive-growth.html (Accessed: November 8, 2025).

IGF (2023) ASEAN-IGF Minerals Cooperation: Scoping study on critical minerals supply chains in ASEAN.

International Energy Agency (2025) Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025 – Analysis – IEA. International Energy Agency (IEA). Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2025 (Accessed: November 8, 2025).

Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (2023) Stockpiling : Metals : Stockpiling | Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMEC). Available at: https://www.jogmec.go.jp/english/stockpiling/stockpiling_10_000001.html (Accessed: November 8, 2025).

Phoumin, H. (2025) Indonesia’s Strategy toward Critical Minerals and Cooperation with the United States | The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). Available at: https://www.nbr.org/publication/indonesias-strategy-toward-critical-minerals-and-cooperation-with-the-united-states/ (Accessed: November 8, 2025).

Reichl, C. and Schatz, M. (2022) World Mining Data 2022. Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Regions and Tourism.

U.S. Department of Energy (2023) “Critical Materials Assessment.” Available at: https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2023-05/2023-critical-materials-assessment.pdf.

U.S. Department of the Interior (2025) MINERAL COMMODITY SUMMARIES 2025. U.S. Department of the Interior.

VietnamNet (2025) Vietnam proposes rare earths as a special strategic resource. Available at: https://vietnamnet.vn/en/vietnam-proposes-rare-earths-as-a-special-strategic-resource-2459260.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed: November 8, 2025).

Huong-Giang Nguyen (NUS Business School), Hieu-Long Hoang(ABL), Pham Thi Cam Anh (Foreign Trade University)