- Circularity in Sustainable Packaging Exports

Over the past five years, sustainable packaging has moved from a peripheral branding choice to a central condition for access to high-value export markets. What distinguishes the current phase is the way circularity—design for recyclability, recycled content, reuse systems, and end-of-life responsibility—has been embedded into market-entry rules, procurement standards, and buyer specifications along international supply chains. In effect, circular performance has become a non-tariff trade requirement: exporters that cannot document recyclability and material recovery increasingly face exclusion or price discounts in the European Union (EU), Japan, and Korea (European Commission, 2024; WTO, 2023). This shift is catalyzed by two reinforcing forces: a rapid tightening of packaging legislation in destination markets, and a reorganization of global plastics flows following Asia’s resource-circulation policies and China’s earlier waste-import bans (OECD, 2025).

Figure 1. Global sustainable packaging market size, 2018–2030 (USD billion)

Figure 1. Global sustainable packaging market size, 2018–2030 (USD billion)

Source: Grand View Research (2024)

European regulatory leadership and spillovers to trade. The EU’s proposed Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) sets the tone for global circular trade in packaging by requiring that all packaging placed on the EU market be recyclable by 2030, with design-for-recyclability criteria, labeling harmonization, and escalating recycled-content targets in plastics (European Commission, 2024; Reuters, 2024a, 2024b). In parallel, the Single-Use Plastics framework mandates 25% recycled content in PET beverage bottles by 2025 and 30% across plastic beverage bottles by 2030, alongside high collection targets supported by deposit-return systems (European Commission, 2024). These rules work in tandem with the broader Green Deal agenda and carbon measures, effectively internalizing life-cycle externalities into market access. For non-EU exporters, compliance has migrated from “nice to have” to “license to operate.” The immediate trade implications are threefold: (i) a premium for converters that can source certified recycled resins (especially rPET and rHDPE) and document traceability; (ii) demand growth for recyclable mono-materials, fiber-based solutions, and compostable applications with robust standards; and (iii) a squeeze on multi-layer, hard-to-recycle laminates without credible design changes (European Commission, 2024; WTO, 2023).

Asia’s resource-circulation turn and buyer pull: On the demand side, global brands (food, beverage, personal care) increasingly embed circular KPIs into supplier contracts, cascading EU-style requirements through Asia-based value chains. On the policy side, producer-responsibility regimes in Japan and Korea push domestic markets toward closed-loop systems and high-quality recycling, indirectly shaping import specifications for packaging and components (Japan Ministry of the Environment, 2021; Korea Environment Corporation, n.d.). Japan’s Plastic Resource Circulation Act (effective 2022) operationalizes “3R+Renewable” across the plastic life cycle, incentivizing design for recyclability and certified recycled inputs (Japan Ministry of the Environment, 2021; JCPRA, 2023). Korea’s long-standing EPR framework, reinforced by the Fundamental Act of Resource Circulation, sets mandatory recycling obligations for packaging materials and imposes charges for non-compliance (Korea Environment Corporation, n.d.; ERIA/RKC-MPD, n.d.). These measures raise the baseline expectations for exporters selling into advanced Asian markets, accelerating convergence toward EU-style circularity.

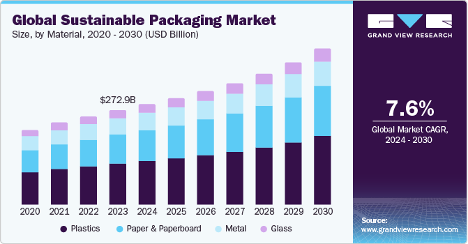

Figure 2. Potentials of the sustainable packaging market (USD billion)

Source: Towardpackaging (2024)

Global supply reconfiguration: recycled feedstocks and secondary materials trade. The OECD’s Regional Plastics Outlook shows that effective recycling rates in East and Southeast Asia have been improving (albeit from a low base), with a strong policy push for quality-controlled recycling and reduced leakage (OECD, 2025). As recycled content mandates tighten in destination markets, cross-border trade in secondary materials (e.g., rPET flakes, rHDPE pellets, de-inked fiber) gains strategic importance. However, “circular trade” will only scale when exporters can prove quality, safety, and traceability of recycled inputs—areas where harmonized standards and credible certification are still consolidating (WTO, 2023; OECD, 2022). At the same time, UNCTAD notes a complementary surge of innovation and trade in plastic substitutes—from fiber-based and compostable packaging to seaweed-derived biopolymers—opening parallel export niches but also posing challenges of performance, infrastructure compatibility, and genuine end-of-life benefits (UNCTAD, 2025).

Market trajectories and product-system shifts. Industry trackers indicate a robust growth path for sustainable packaging, driven by regulation-induced demand and retailer commitments. While estimates vary by methodology, multiple analyses concur on a multi-hundred-billion-dollar market by 2030; the common denominator is faster growth for recyclable mono-material solutions, rPET/rHDPE-based rigid packaging, and fiber-based formats displacing mixed laminates in regulated categories (Grand View Research, 2024; Transparency Market Research, 2022). Yet circularity is not only a material story; it is increasingly a system story: deposit-return for beverage containers, reusable transport packaging in e-commerce logistics, and standardized eco-modulation of EPR fees that reward design improvements. Exporters that plug into these systems—by offering DRS-ready bottles, reuse-compatible transit packaging, digitally traceable labels, or certified recycled content—can command better acceptance and margins in regulated markets (European Commission, 2024; WTO, 2023).

Implications for latecomer exporters. For developing-economy producers, the opportunity lies in moving from linear conversion to circular solutions. Converters that previously competed on low-cost lamination now face a step-change toward design for disassembly, mono-material films, water-based inks, and food-grade recycled inputs. Documentation (recyclability protocols, chain-of-custody for r-materials), conformity assessment, and alignment with destination-market labeling are becoming as critical as price and lead time. Countries that enable exporters with testing capacity, recognized certification, and access to recycled feedstocks (food-grade rPET, deodorized rHDPE, high-yield reclaimed fiber) will gain share in the sustainable packaging export segment (OECD, 2022; OECD, 2025). Conversely, jurisdictions that remain tied to multi-material laminates without credible end-of-life pathways risk rising compliance costs, retailer delistings, or outright market loss as PPWR-style rules crystallize (European Commission, 2024; Reuters, 2024a, 2024b).

Finally, the trade governance layer is evolving to support this transition. Within the WTO’s TESSD track, members are mapping ways to reduce barriers on environmental goods and improve transparency around circular standards, eco-labeling, and conformity assessment—precisely the friction points that now determine whether a “green” package is tradable at scale (WTO, 2023). For exporters in Asia, alignment with EU/Japan/Korea protocols, mutual recognition of testing, and participation in regional resource-circulation frameworks are becoming prerequisites to compete in a world where circular performance is inseparable from trade performance (ASEAN Secretariat, 2021; OECD, 2022).

- Vietnam’s Current Situation: Transitioning toward Sustainable Packaging Exports

2.1 Industry Overview

Vietnam’s packaging industry has expanded rapidly over the last decade, mirroring the country’s deeper integration into global manufacturing value chains. According to the Vietnam Packaging Association (VPA, 2024), the sector reached an estimated USD 17 billion in 2024, growing at an average CAGR of 12–14 percent since 2015. Around 14 000 enterprises operate nationwide—mostly small and medium-sized converters (≈ 85 percent domestic, 15 percent FDI).

Exports of packaging materials and products, particularly plastic films, paper cartons, and corrugated boxes, reached USD 8.8 billion in 2022, up from USD 5.1 billion in 2015 (Vietnam Briefing, 2024).

The sector remains dominated by plastics. Between January and July 2025, Vietnam imported 5.55 million tons of virgin plastic resin valued at USD 7.3 billion—an increase of 18.8 percent in volume and 11.6 percent in value year-on-year (B-Company Japan, 2025).

Polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) comprise over 80 percent of resin consumption, while domestic resin production covers only about 20 percent of demand (OECD, 2025). The paper-packaging segment has also grown strongly, driven by e-commerce and export logistics: national output reached 4.5 million tons in 2023, worth about USD 3.5 billion (Paper Vietnam, 2024).

Despite the growth, the overall system remains linear—“make-use-dispose.” Only 15–20 percent of post-consumer packaging waste is formally recovered for recycling, and nearly all collection depends on the informal sector (MONRE, 2024). Of roughly 3 500 plastic-recycling facilities, only ≈ 300 meet basic environmental or food-grade standards (World Bank, 2023).

As a result, Vietnam continues to export low-value, single-use packaging while importing higher-value recycled resins to satisfy EU and Japanese buyers’ circular-content requirements (UNIDO, 2023).

Table 1. Market size of Vietnam’s packaging industry by material (2015–2025)

| Year | Plastics

(USD bn) |

Paper & Paperboard

(USD bn) |

Others

(USD bn) |

Total

(USD bn) |

| 2015 | 5.3 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 7.6 |

| 2020 | 8.7 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 12.0 |

| 2024 | 12.0 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 17.0 |

| 2025 (f) | 12.9 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 18.4 |

(Data source: VPA 2024; Vietnam Briefing 2024)

2.2 Policy and Institutional Framework

Vietnam’s shift toward circular packaging has been policy-driven only since 2020 but is accelerating through a mix of environmental, industrial, and trade instruments.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): The 2020 Law on Environmental Protection (LEP) and Decree No. 08/2022/NĐ-CP established Vietnam’s first binding EPR system, operational from January 2024. Producers and importers of packaging must either (i) organize collection/recycling of a mandated proportion of packaging waste or (ii) pay a recycling fee into the Vietnam Environmental Protection Fund (VEPF). Targets are 22 percent (plastics) and 25 percent (paper) by 2025, rising to 45 and 50 percent respectively by 2030 (MONRE, 2024). Eco-modulated fees incentivize recyclable designs and penalize multi-layer laminates, consistent with OECD best practice (OECD, 2025). Five pilot Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs) were registered under VEPF supervision by mid-2025 (VEPF, 2025).

Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP 2022): Issued under Decision 687/QĐ-TTg, the CEAP identifies packaging and plastics as priority sectors for pilot circular projects. It promotes reverse-logistics infrastructure and industrial symbiosis zones where waste from one plant becomes raw material for another. The UNDP–MONRE Circular Economy Hub Vietnam (2023) catalogs ongoing pilots such as Tetra Pak’s beverage-carton recycling line in Binh Duong and Duy Tân’s bottle-to-bottle project in Ho Chi Minh City (UNDP, 2023).

National Green Growth Strategy (2021–2030): Decision 1658/QĐ-TTg sets three packaging-related targets: (1) cut virgin-plastic use by 30 percent by 2030;

(2) collect and recycle 85 percent of packaging waste; and (3) ensure 40 percent of export products meet environmental certification (MPI, 2023). It also mandates green public procurement and credit lines through the Vietnam Development Bank for eco-industrial projects.

Trade and FTAs: Vietnam’s new-generation FTAs reinforce these domestic reforms. The EU–Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA) includes Chapter 13 (Trade and Sustainable Development) promoting eco-labeling, waste management, and low-carbon goods (European Commission, 2023). Similarly, the CPTPP and UKVFTA contain environmental cooperation clauses, encouraging alignment with international circular-trade standards. This gives Vietnamese exporters a framework to meet EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR 2024) and Japan’s Plastic Resource Circulation Act (2022) requirements (OECD, 2025).

However, institutional fragmentation persists: MONRE manages EPR; MOIT oversees industrial policy; MARD handles paper and biomass; and Customs lacks traceability systems to verify recycled content. A draft National Circular Economy Decree (2025) seeks to harmonize these mandates (MONRE, 2025).

2.3 Value Chain Mapping

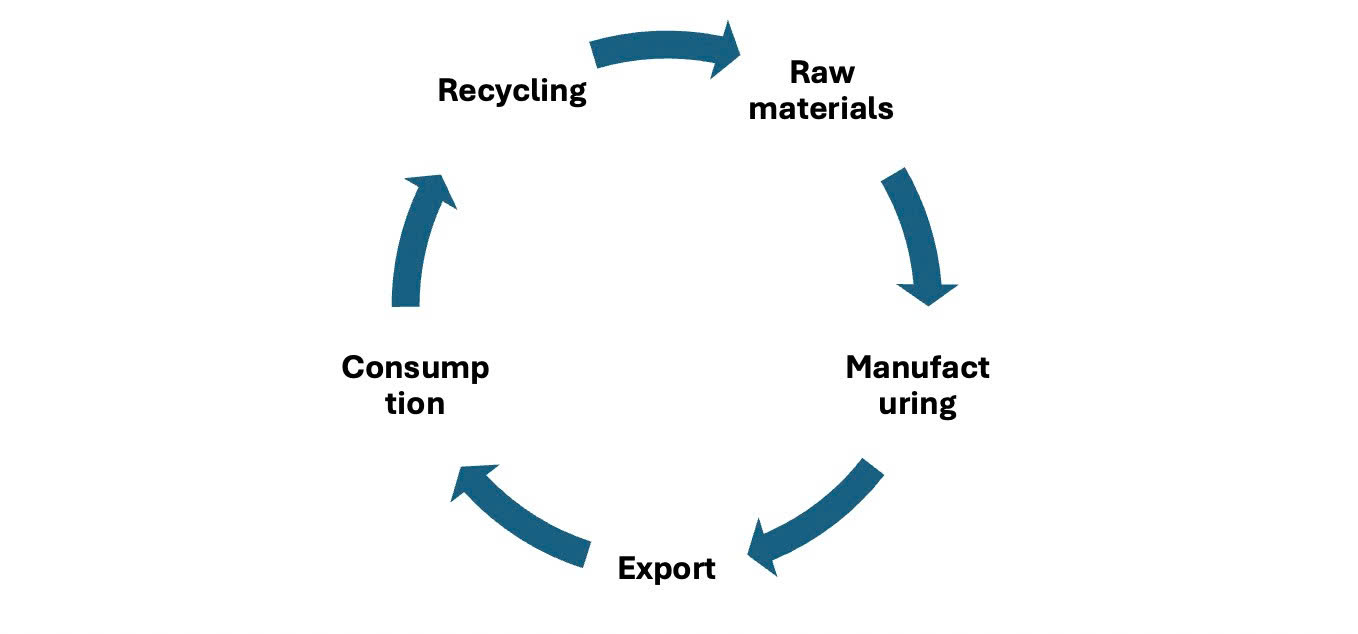

Vietnam’s packaging value chain can be divided into four stages—inputs, processing, distribution/export, and post-consumer recovery—each revealing points where circular interventions can add value.

Inputs: Feedstock supply is heavily import-dependent. In 2024, resin imports exceeded USD 10 billion, primarily PET, PP, and PE (General Department of Customs, 2024). Domestic production of bioplastics remains limited; An Phát Bioplastics’ PLA/PHA facility in Hai Phong (20 000 tons/year) covers less than 1 percent of national demand (An Phát Holdings, 2024).

Local recycled-resin capacity reached ~250 000 tons/year in 2025, meeting only 8 percent of domestic consumption (OECD, 2025).

Processing: Technology heterogeneity defines the sector. Large FDI plants (Tetra Pak, SCG Packaging, JSP Vietnam) apply modern printing and lamination technologies, whereas ≈ 80 percent of SMEs use second-hand equipment. Average labor productivity is USD 32 000/employee/year, about half of Thailand’s (OECD, 2025). Only ≈ 10 percent of firms possess ISO 14001 or BSCI certification, limiting access to high-end export markets (VPA, 2024).

Distribution and Exports: Packaging exports rose 72 percent between 2015 and 2022 (VPA, 2024). The United States, Japan, and the EU remain top buyers. Yet just 10 percent of exported packaging contains verified recycled content (World Bank, 2023). In contrast, Thailand and Malaysia already exceed 30 percent due to established rPET/rHDPE supply chains.

Post-consumer Recovery and Recycling: Recycling rates are modest: PET/HDPE/PP ≈ 32–45 percent (Eunomia, 2022). Informal collectors (≈ 400 000 nationwide) remain the backbone of recovery (World Bank, 2023). New EPR PROs seek to formalize this network and finance collection centers through fee revenues. The target is to build five regional reverse-logistics hubs by 2030 (MONRE, 2025).

Table 2. Vietnam Packaging Value Chain – Circular Transition Leverage Points

| Stage | Current Status | Circular Opportunities | Constraints |

| Input Materials | 80 % imported virgin resin | Expand domestic rPET/rHDPE; bio-based resins | Quality & traceability of recyclates low |

| Processing | SME dominance; outdated tech | Eco-design, light-weighting, water-based inks | Limited finance & know-how |

| Distribution/Export | Rising exports (USD 8.8 bn 2022) | Eco-labels, digital traceability, reuse systems | Cost burden; non-uniform standards |

| Recycling | 32–45 % rate; informal collection | PROs, reverse logistics, industrial symbiosis | Weak infrastructure & data sharing |

(Source: Author’s compilation based on VPA 2024, MONRE 2024, World Bank 2023)

2.4 Challenges and Transition Dynamics

Governance fragmentation: Circular economy governance remains siloed. MONRE enforces EPR but lacks integration with trade authorities to track recycled-content exports. MOIT’s green-industry program focuses on energy efficiency rather than material circularity. Provincial implementation varies—Ho Chi Minh City and Binh Duong have advanced pilots, while northern provinces lag (MONRE, 2024). A planned National Circular Economy Council (2026) aims to coordinate these efforts (VCCI, 2025).

Infrastructure and technology gaps: Vietnam has only four food-grade rPET plants (total capacity < 50 000 tons/year) compared to Thailand’s 200 000 tons (OECD, 2025). Testing labs for migration and toxicity are scarce; exporters must outsource certification to foreign labs, raising costs by 10–15 percent per shipment (European Commission, 2024). Bioplastic manufacturing remains limited to An Phat and a few start-ups in Binh Duong and Hai Phong.

Finance and SME readiness: For SMEs, the cost of adopting eco-design and traceability systems equals 10–15 percent of annual revenues (VPA, 2024). Only three domestic banks offer green credit lines (MPI, 2023). International initiatives like the World Bank’s Green Innovation Grant and UNIDO’s Eco-Packaging for SMEs Vietnam (2023–2025) have supported just 40 firms nationwide. Scaling finance is critical to extend benefits to thousands of converters outside industrial zones.

Market and regulatory pressures: Destination-market requirements (EU PPWR, Japan PRC Act) will tighten by 2030, making non-recyclable exports commercially unviable. Under EVFTA rules, eco-labeling and life-cycle information disclosure are becoming mandatory for suppliers to EU buyers. Without upgraded traceability and EPR compliance, Vietnamese exporters risk margin erosion or market loss (OECD, 2025). Conversely, firms that pivot early toward circular solutions could differentiate themselves in premium markets.

Social and labour dimensions: The informal recycling sector provides livelihoods for hundreds of thousands of workers, mainly women and migrants. Formalizing this workforce through PROs and municipal cooperatives is essential to avoid social disruption while raising collection efficiency (World Bank, 2023). Pilot programs in Ho Chi Minh City show that formal contracts with waste-picker groups increase collection rates by 30 percent and reduce leakage (OECD, 2025).

Figure 3. Packaging Value Chain and Circular Transition in Vietnam

(Source: Author based on VPA 2024; MONRE 2024; World Bank 2023.)

Vietnam’s packaging industry is transitioning from a volume-driven, export-assembly model to an innovation-driven, circular one. Policy reforms—especially EPR, CEAP, and green FTAs—lay a foundation for integration into global circular value chains. Yet implementation gaps in infrastructure, finance, and institutional coordination persist. If addressed through targeted investment, regulatory alignment, and public–private partnerships, Vietnam could position itself as a regional hub for sustainable packaging exports by 2030. The transition offers economic upgrading opportunities and supports Vietnam’s commitments under the Paris Agreement and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

- Policy Implications

Vietnam’s path from a linear, resource-intensive packaging model toward a circular export system depends on whether its trade, industrial, and environmental policies can evolve in sync. The challenge lies less in policy intent—already visible through the Law on Environmental Protection 2020, the Circular Economy Action Plan 2022, and the Green Growth Strategy 2030—than in execution, financing, and international alignment. To remain competitive as global markets tighten recyclability and carbon-content standards, Vietnam must strengthen coordination, investment, and trade diplomacy around circular value chains.

First, coherence across ministries is essential. Responsibilities for extended producer responsibility (EPR), industrial upgrading, and export promotion remain fragmented among MONRE, MOIT, and MPI, delaying implementation. Establishing a National Circular Economy Council to coordinate trade and environment strategies would accelerate progress. Within it, a Circular Trade Unit could track recycled-content flows, manage certification databases, and liaise with customs to integrate circular metrics into export statistics—functions already proven effective in Japan’s and the EU’s circular-governance systems (European Commission, 2024; JCPRA, 2023).

Second, infrastructure and finance form the backbone of circular competitiveness. Recycling capacity in Vietnam—around 250 000 tons of rPET/rHDPE annually—covers less than 10 percent of national demand (OECD, 2025). Expanding food-grade recycling, reverse-logistics hubs, and industrial symbiosis parks would reduce import dependence and leakage. Revenues from the new EPR system could seed a Green Transformation Fund for Packaging, co-financing equipment upgrades, digital traceability tools, and eco-design R&D. Public procurement and export-credit schemes should also privilege suppliers using verified recycled content, translating environmental behavior into market advantage.

Third, international cooperation can transform compliance into opportunity. Through the EU–Vietnam FTA and ASEAN’s Circular Economy Framework, Vietnam can negotiate mutual recognition of eco-labels and recycled-content certificates, cutting testing costs and border delays. Participation in regional and plurilateral initiatives such as DEPA or IPEF would enable the country to pilot digital product passports and cross-border waste-traceability platforms. Embedding such standards into customs procedures would make “circular trade facilitation” a competitive asset rather than an administrative burden.

A further priority is enabling small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which constitute most packaging converters yet lack capital for eco-innovation. Expanding green-credit lines under the State Bank’s sustainability framework and introducing partial-guarantee mechanisms could unlock private investment. Technical-training programs, jointly developed by MOIT, VCCI, and UNIDO, should focus on eco-design, material substitution, and environmental reporting. Simultaneously, the informal waste-collection sector—about 400 000 workers, predominantly women—must be integrated into EPR implementation through formal contracts with Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs). International evidence suggests that such inclusion improves collection rates by 30 percent while stabilizing incomes (World Bank, 2023).

Finally, transparency and standards are critical for credibility in export markets. Developing national recyclability and compostability standards (TCVN series) harmonized with the EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation 2024 would help local producers demonstrate compliance. A QR-based “Packaging Passport” linked to customs and EPR databases could trace material origin and recycling performance, aligning with upcoming global digital-passport regimes.

If implemented cohesively, these reforms could lift Vietnam’s packaging-recycling rate to 45–50 percent and boost circular-export revenues beyond USD 25 billion by 2030, while formalizing thousands of jobs and reducing material imports. More importantly, they would reposition Vietnam from a cost-driven converter to a regional leader in sustainable-packaging trade, supplying circular solutions—not waste—to the global market.

References

- An Phát Holdings. (2024). Corporate sustainability report: Bioplastics development in Viet Nam. Hai Phong: An Phát Holdings.

Retrieved from https://www.anphatholdings.com - ASEAN Secretariat. (2021). ASEAN Circular Economy Framework. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat. Retrieved from https://asean.org/our-communities/economic-community/asean-circular-economy-framework

- ASEAN Secretariat. (2021). ASEAN Circular Economy Framework. Jakarta: ASEAN.

European Commission. (2024). Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR). Brussels: Publications Office of the EU.

Japan Containers and Packaging Recycling Association (JCPRA). (2023). Plastic Resource Circulation in Japan. Tokyo: JCPRA. - Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI). (2023). National Green Growth Strategy 2021–2030. Hanoi: MPI.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2025). Regional Plastics Outlook for Southeast and East Asia. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). (2023). Eco-Packaging for SMEs Vietnam Pilot Project. Vienna: UNIDO.

- Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI). (2025). Proposal for National Circular Economy Council. Hanoi: VCCI.

- World Bank. (2023). Toward a Circular Economy in Vietnam: Opportunities for a Green Recovery. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- B-Company Japan. (2025). Vietnam’s plastic resin market – Industry landscape and foreign investment opportunities. Tokyo: B-Company Japan.

Retrieved from https://b-company.jp/vietnams-plastic-resin-market-industry-landscape-and-foreign-investment-opportunities - Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2019). Completing the picture: How the circular economy tackles climate change. Cowes, UK: Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

Retrieved from https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/completing-the-picture - Eunomia Research & Consulting. (2022). Vietnam recycling rate and cost report 2022. Bristol, UK: Eunomia. Retrieved from https://www.eunomia.co.uk/reports-tools/vietnam-recycling-rate

- European Commission. (2023). EU–Vietnam Free Trade Agreement, Chapter 13: Trade and Sustainable Development. Brussels: European Union.

Retrieved from https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/vietnam_en - European Commission. (2023). European Green Deal and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Brussels: European Union. Retrieved from https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

- European Commission. (2024). Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR). Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/packaging-waste_en

- General Department of Customs (Vietnam). (2024). Statistical yearbook of import–export activities 2023. Hanoi: Vietnam Customs.

- Gereffi, G. (2018). Global value chains and development: Redefining the contours of 21st-century capitalism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108448151

- Japan Containers and Packaging Recycling Association (JCPRA). (2023). Plastic Resource Circulation in Japan – Annual Report 2023. Tokyo: JCPRA.

Retrieved from https://www.jcpra.or.jp/english - Japan Ministry of the Environment. (2021). Act on Promotion of Resource Circulation for Plastics (Plastic Resource Circulation Act, No. 60 of 2021). Tokyo: Government of Japan.

Retrieved from https://www.env.go.jp/en/ - Korea Environment Corporation. (n.d.). Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) System in Korea. Seoul: Ministry of Environment (MOE).

Retrieved from https://www.keco.or.kr/en/ - Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE). (2024). Report on EPR implementation progress in packaging. Hanoi: MONRE.

Retrieved from https://en.monre.gov.vn/ - Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE). (2025). Draft National Circular Economy Decree. Hanoi: MONRE.

- Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI). (2023). National Green Growth Strategy 2021–2030. Hanoi: MPI.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2022). Trade and circular economy: Practices and lessons learned from Asia and the Pacific. Paris: OECD Publishing. DOI: 10.1787/aa1edf0e-en

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2025). Regional plastics outlook for Southeast and East Asia. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/publications/regional-plastics-outlook-for-southeast-and-east-asia-5a8ff43c-en.htm - Paper Vietnam Conference. (2024). Vietnam paper packaging market: Average potential growth rate of 9.73 % per year. Retrieved from https://paper-vietnam.com/vietnam-paper-packaging-market-average-potential-growth-rate-of-9-73-year

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2023). Circular economy and trade: Opportunities for developing countries. Geneva: United Nations.

Retrieved from https://unctad.org/publication/circular-economy-and-trade - United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). (2023). Eco-Packaging for SMEs Vietnam Pilot Project – Progress Report. Vienna: UNIDO.

- Vietnam Briefing. (2024). Vietnam’s packaging industry: Investment outlook and sustainability trends 2024. Hanoi: Dezan Shira & Associates. Retrieved from https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/vietnams-packaging-industry-investment-outlook.html

- Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI). (2025). Proposal for establishing a National Circular Economy Council. Hanoi: VCCI.

- Vietnam Packaging Association (VPA). (2024). Industry report on sustainable packaging exports 2024. Hanoi: VPA.

- World Bank. (2023). Toward a circular economy in Vietnam: Opportunities for a green recovery. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099450323010622182/p17701308008e809090e90509b8b0e7a90c

- World Trade Organization (WTO). (2023). Trade and Environmental Sustainability Structured Discussions (TESSD) – Annual Report 2023. Geneva: WTO. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tessd_e.htm