In his keynote address, Dr Smeets discussed how the economic trade and investment landscape is rapidly changing due to the technological advances and its likely implications for trade and competition between the main economic actors, including the US, China and the European Union. Competition is increasingly technology driven and changing the way we live, consume, interact and business is conducted. The Covid pandemics has accelerated this process and put technology at the center of competition in world markets. It has triggered a new wave of industrial policies in support of technology intensive production, involving unprecedented amounts of government subsidies and such on three continents, including North America, Asia and Europe.

This process has triggered a drive to decrease dependency of foreign suppliers and hence generated a gradual retreat from globalization as we have seen evolving since the 1980-es at least in its original form. While evidence confirms that globalization has in fact brought tremendous economic benefits to consumers and producers alike, there are fears that globalization has gone too far and made economies too vulnerable. It has triggered a change of course, with a rise of nationalism, protectionist measures and policies focusing on bringing production back home. This is mostly referred to as de-globalization with calls for ‘re-shoring’, ‘near-shoring’ and ‘friend-shoring’. Whether this means the end of globalization is doubtful or at least questionable, but surely there is a common sense that the concept need revisiting. The question is what is the best way forward, serving both the domestic and common interests? Do we really know who are our friends and how reliable will they be for securing viable and stable Global Value Chains (GVCs) and supply lines?

These course changes of relocating economic and production activities closer to home have significant implications for trade and investment flows, with a stronger domestic and regional focus for investment. It is driven by the notion of self reliance for reasons of national security and decreasing dependency on foreign supplies in essential goods. This very much goes against the logic of the classical trade theories, based on comparative advantage and specialization. In order to achieve these objectives, countries are increasingly determined to implement domestic industrial policies in support of essential and strategic industries and ‘de-coupling’ and ‘building back better’ and thus making supply lines more resilient. As the saying goes: a chain is as strong as its weakest link. Geo- and socio, economic, political developments as well as Covid-19 have evidenced a need to make supply lines more resilient. The challenge and key question remains whether these new policies strengthen the GVC link?

Today we witness an increasingly strong determination by governments to introduce policies in support of the high technology sectors and industries. Governments are now conducting highly active and costly industrial policies in support of their domestic industries and more specifically in those sectors that are likely to generate the highest value addition. What do these policies consist of and who are the players? It is a multi billion dollar subsidy race mostly taking place in the United States, Asia and followed by Europe. Each of them have their own variation of the Chips act and laws in support of strengthening the domestic infra-structures, costing billions if not trillions of dollars. The ultimate goals is to decrease dependency of foreign suppliers and building a viable independent industry and perhaps even achieving technological supremacy and dominating the world markets.

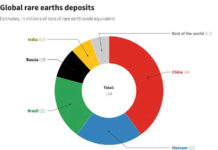

A retreat from international cooperation however is not the solution and such can not be the right reaction in an increasingly interdependent world. To the contrary, the digital economy has brought markets, consumers and countries ever more closely together, requiring more international cooperation and coherence in policies. It is recognized that i order to strengthen an economy’s resilience, there is a need for a diversification of supply lines, thus decreasing a country’s vulnerability in case of a supply-shock. However, and instead of following purely nationalistic and going-alone policies, there are alternative, more efficient and cooperative ways of achieving that goal. These include a diversification of suppliers, instead of depending on a single supplier, relocating some of the production closer to the home market, even if this means a higher economic cost and cooperating both at the regional and a more global level. In part this is already happening with new inward FDI flows in the high tech industries, but also a stronger concentration of production at the regional level, especially in Asia. The need to cooperate is further dictated by the fact that many of the essential inputs into high technology production are geographically dispersed. Rare earth, nickel, cobalt, lithium are all scarce resources and found and extracted only in a few places, including in Africa.

The cooperative efforts at the international level are still weak, if not absent and hence the inter-continental trade frictions and rivalry in the high tech sector. The WTO has an important role to play in order the strengthen and deepen international cooperation, develop converging policies and updating the WTO’s multilateral trade rules for e-commerce and Investment. While efforts are underway to agree on the so-called joint initiatives on e-commerce and Investment Facilitation for Development, the process is slow and the outcome uncertain. Some Members contest these plurilateral initiatives and some want to end the e-commerce moratorium, which ensures duty free digital trade transactions.

As a result, and in the absence of multilaterally agreed trade rules, countries are following regional approaches and with a view of creating convergence of policies at the regional level. This includes rules on e-commerce, competition policies, investment etc., all areas that have been left out of the multilateral trade rules. These regional approaches certainly ease the creation of regional production hubs, GVCs and supply lines at the regional and perhaps more local level. However, they entail a serious risk of deepening the polarization and conflicting approaches, standards and rules in different regions and between trading partners, thus raising the cost of transactions and reducing security and stability in international trade. Hence the call for reinvigorating and strengthening efforts to build global rules at the multilateral level.